Few sounds pierce the human heart like a wolf’s howl. Whether the call elicits terror, wonder, or both hinges on perspective and circumstance, but the evocative melody will surely stir the listener. Because for many, the wolf represents more than a wild canid. It represents the wild itself, both out there, deep in the forest most of us would die in if not well-provisioned, and in ourselves. For others, the wolf is a threat to our livelihoods. It’s a competitor if not an adversary. And, for some, the wolf is still a beast in the night–that other lurking just beyond the glow of the campfire, the village, or the porch light…waiting for us to stray too far and rip us apart.

As a non-rancher living in modern-day North America, I have the luxury of viewing wolves through that first lens. I don’t need to worry about them. They’re probably not even here. Hunted mercilessly, they were extirpated from Maine in the 1890s. But if some have crept back down from Canada as many claim, I wouldn’t be any more concerned for my or my daughter’s safety with wolves in the abutting forest than I am with our abundant black bears or our decidedly wolfy coyotes (which is close to not at all). Unprovoked attacks on humans by healthy wild wolves in North America are almost unheard of.

The same can’t be said of the Old World. My not-so-distant European ancestors had good reason to worry. Where people lived in high density alongside wolves for centuries and wars put piles of human meat out for scavenging, Canis lupus was a different beast.

While many historical accounts of man-eating wolves are likely exaggerated, plenty have been recorded. It would be naïve to deny that wild wolves have sometimes become anthropophagous (man-eating).

The most infamous of these wolves is believed to be the Beast of Gévaudan.

The Carnage

In 1764, in the former region of Gévaudan in southern France, a series of bizarre animal attacks began that historians, biologists, cryptozoologists, and even some paranormalists still discuss today.

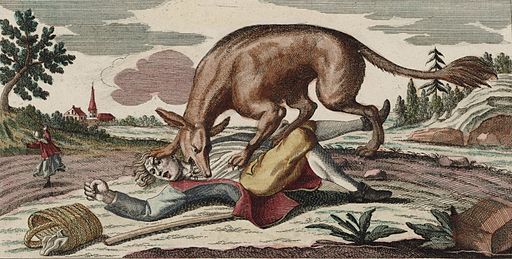

La Bête, the beast, attacked at least ninety-nine people in less than two years, fifty-three of which it killed. Some writings claim a much higher death toll, but the first official victim was 14-year-old shepherdess Jeanne Boulet. She led her charges up to a highland pasture near the border of the Gévaudan region and never returned. Her body was found the next day. Most of those attacked were women and older children, especially teenagers. Victims were often taken while tending livestock. The bloodshed was so great that the local bishop claimed the attacks were a divine scourge meant to punish the sinful populace, calling for prayers and more virtuous behavior.

King Louis XV was a bit more pragmatic, sending expert huntsmen after the beast once tales of the monster reached his ear. Francois Antoine shot a sizable wolf that reportedly bore a bayonet wound from twenty-year-old Marie-Jeanne Vallet, who had speared it with a makeshift weapon when attacked. But the killings only stopped for a month, and the death toll crept up once again. For almost three years, the beast terrorized Gévaudan and the surrounding areas. Only after Jean Chastel, a local farmer, shot a large wolf did the attacks stop. The last documented victim was nineteen-year-old Jeanne Bastide.

La Bête

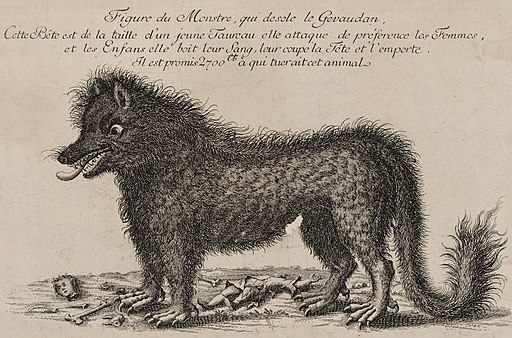

Besides the massive body count for a single canid, if the culprit was indeed one wolf, the beast had several unique characteristics. Survivors and witnesses described a tawny or reddish-colored animal, sometimes with stripes, particularly a thick strip of long, dark fur down the back. Some reported a long, tufted tail and finger-length claws. La Bête was said to be incredibly strong and able to leap great distances. It was powerful enough to carry older children and adults away. Observed attacks were primarily by ambush. The beast was sometimes reported to hold down victims with its forelimbs and smother or strangle them, presumedly by clamping its jaws over the face or throat. Several victims were decapitated. La Bête appeared to target humans, ignoring most livestock (though it allegedly leaped upon horses), and a few human victims were even saved by the animals they were tending.

One might notice that la Bête’s observed appearance and behaviors are not typical of wolves. Some are absolutely inconsistent with a wolf’s morphology.

Hence the enduring mystery of la Bête. Was it a wolf? Most historians seem to say no–it was several wolves. But an anthropophagous pack or multiple rogues explain little more than the extreme body count. It doesn’t begin to address la Bête’s strange appearance or some of its feats.

Unless you write off all the beast’s anomalous traits as the products of hysteria, spin, and superstition. Might the tragically disadvantaged peasantry have granted the creature terrorizing them extraordinary strength and agility? Gigantic size? Supernatural abilities? Sure. But why add the strange fur and tail? If my village was being ravaged by a wolf, I’d try to describe the offending animal as accurately as possible. That way, hunters and authorities would know what they were after.

Of course, we don’t actually have first-hand accounts from terrified peasants. If any could write, their reports are long gone. The tales we have today have been filtered through the Catholic clergy and nobility.

Could priests have altered the details of eyewitness accounts to make a monster? Maybe. But unlike the region’s bishop, the priests who wrote letters to colleagues and pled to officials for help tended to downplay la Bête’s otherworldliness. Most of their writings suggest a flesh and blood animal, not anything imbued with the supernatural. They also speculated that it wasn’t a wolf. Though some writings of the time called la Bête a wolf or wolf-like animal, others referred to it as a hyena or big cat.

Tawdry Taxidermy

One would think a simple DNA test could tell us definitively what took so many lives in the south-central highlands of France almost 260 years ago. But the mangled corpse of the animal killed by Jean Chastel and purported to be the beast was rather artlessly stuffed with straw after dissection. When it arrived in Paris to be inspected by prominent natural historian Comte de Buffon, it was a rotting abomination. It’s believed la Bête was buried somewhere in the botanical gardens after examination.

But was the slain animal even really la Bête?

The most thorough assessment of the predator killed by Chastel was done locally at Besques castle by medical doctors and recorded by royal notary Roch Étienne Marin. The resultant report concluded that la Bête was a wolf, but one like no other. There are numerous inconsistencies and suspicious claims in the report, however. Taake 2023 delves into these in-depth and speculates that the report’s goal was to make an ordinary wolf seem unusual enough to have been the monster.

Why would anyone pronounce la Bête dead when it wasn’t? Perhaps to quell the understandable hysteria among the peasants. Or to mask the ineptitude of French authorities at the time and save them further embarrassment. At the very least, solving the problem of la Bête would make the local ruling class seem competent.

Yes, the deaths attributed to la Bête stopped after Chastel felled his wolf. They also paused for a month after Antoine shot his wolf. Or did they? Under pressure from the king, authorities may have been inclined to pretend the problem was no more and failed to record official victims during the lull. Witnesses may have been encouraged to positively identify a wolf carcass as la Bête. Perhaps the same was true the second time, and the killings continued quietly awhile, with any deaths being blamed on other animals.

Should we default to conspiracy? Of course not. Concluding that the wolf killed by Chastel was the last of multiple man-eating wolves in the Gévaudan region in the mid-1760s is perfectly reasonable. But some of la Bête’s more distinguishing characteristics were either missing from Chastel’s wolf or went unrecorded, which is bound to stick in some craws.

What, if Not Wolves?

Everyone familiar with la Bête has their pet theory. Here are the most prominent:

Werewolf

Whether or not one allows for the existence of werewolves and similar supernatural creatures, the evidence for this is thin. The best reason to blame a werewolf I can conjure is la Bête’s reputation for shrugging off musket balls and maybe slurping blood from its victims. Perhaps the reports of claws also have something to do with it. But most witness descriptions don’t align with what we think of as werewolves, and there seems to be little mention of them in records of la Bête. Were I to blame a shapeshifter, I’d be more inclined to believe a werehyena migrated north and perpetrated the slaughter.

Serial Killer

The theory here seems to be that a man trained a pet wolf or wolf-dog to kill people. Some folks have implicated Chastel. Although a pet wolf or hybrid is much more likely to attack humans than a wild purebred, there doesn’t seem to be much evidence that a man was directing la Bête. One might argue that dismemberment and decapitation point to human involvement, but some predators handle their prey this way. Some could also point to the number of young women killed by la Bête and interpret this as a victim profile. But it isn’t unusual for predators to target petite women and children. A smaller person usually equals a less risky kill. Besides, the young women of Gévaudon were the individuals most often sent out to tend the herd unarmed. They were put in the path of the beast. Plenty of older individuals and males became victims of la Bête anyhow.

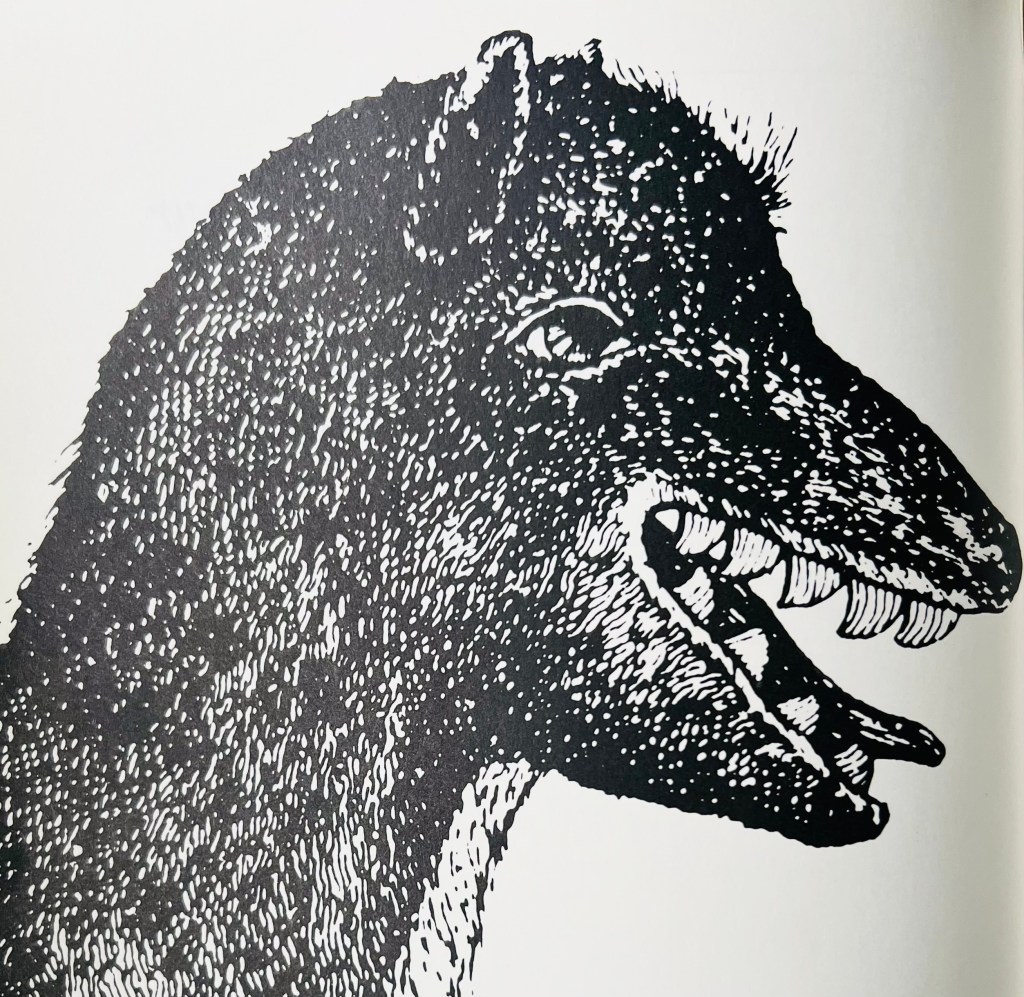

Hyaenodon

I love this theory, mostly because I also love cryptids and prehistoric megafauna. What I find most intriguing is the similarity between reconstructions of the hyaenodon and some of the descriptions of the beast. Even renditions by some 18th-century artists of la Bête look strikingly similar to how paleontologists believe hyaenodons appeared. Of course, some of the features in these reconstructions come from researchers’ imaginations. We can’t know what a hyaenodon’s pelage looked like. What scientists can surmise, though, is that they were predators with large heads and doglike bodies. Based on their feet and forelimbs, they were probably not superb runners. They likely ambushed their prey and held it down with their forelegs. The problem with this theory is that paleontologists believe they went extinct around 20 million years ago. For one to have wreaked havoc into the 1760s, there would have had to have been at least a small population living in the highlands of France for as long as humans have. If that were the case, one would think there would be other documented encounters with these creatures from centuries past.

Striped hyena

I like this theory because descriptions of the beast match a striped hyena pretty closely. In fact, La Bête was called a hyena in some newspapers and correspondence of the time! And though hyenas are more closely related to cats, they appear doglike. Someone familiar with wolves but not hyenas might call one wolf-like. Had the beast been recognizable as a wolf, I think victims and survivors would have called it a wolf. The horror of the incidents might have driven them to call it a gigantic, evil wolf with hellfire gleaming in its eyes and razor-sharp fangs, but still—a wolf. Hyenas are larger than the average wolf, and they are known to attack people. They’re capable of dismembering bodies and even have a history of ripping pieces off when people are still alive. No, there weren’t wild populations of hyenas in France in the 1760s. But it’s not hard to imagine one slipping away from some noble’s private menagerie (another reason for authorities to point at Chastel’s wolf rather than acknowledge culpability for the Gévaudon nightmare). The reason I don’t fully back the hyena theory is that, as far as I know, there haven’t been hyenas on record who forsake all other prey and rack up incredible body counts in a couple of years. The typical unprovoked hyena attack seems to occur when people sleep outdoors and a hungry animal ambles by.

Big Cat

An escaped big cat is an excellent candidate for la Bête’s true identity, in my opinion. The most prolific maneaters in history are the big cats. The famous lion pair of Tsavo ate as many as 135 railroad workers. Not to be outdone, the leopard of Rudraprayag by itself had a body count of 125, the Panar leopard had 400 official victims, and the tigress of Champawat reportedly killed 436 Nepalese and Indians in the Himalayan foothills. The worst offenders of all were likely the Njombe lions, a pride believed to have slain more than 2000 people in their long tenure. These killer cats were active in the 20th century or just before it. Gods know how many they killed before firearms existed. Besides the precedent set by these prolific maneaters, cats are ambush predators, often hunting and killing as described in accounts of la Bête. They can easily drag even adult men away and dismember a human body.

And when a lion gets the taste for people, we tend to be all it hunts. La Bête was said to ignore the livestock and go for the shepherds. Another clue that la Bête might have been a lion is that it cracked open the skull of ~60-year-old Catherine Vally and licked the insides clean. Human-eating lions are known for this behavior. Although descriptions of the beast match a hyena more closely than a lion, if you ask me, Taake 2020 makes an excellent case for why la Bête could have been a subadult male lion. Honestly, I buy it. And some witnesses did describe la Bête as lionlike or catlike. Two things make me doubt (slightly) that the beast was a lion, though. The first is that the proportion of victims who survived seems high for lion attacks. Almost half of la Bête’s recorded victims lived. I think even a scraggly subadult would have been more lethal, especially knowing how often wounds by big cat claws turn septic and the poor state of medicine at the time. I also wonder why no one could identify it as a lion definitively. No, the shepherds may not have owned illustrated books or had the opportunity to visit a menagerie. But lions appear in the Bible. Might not some of the rural populace have seen religious (or royal) imagery depicting these animals?

Wolves

While there will always remain the possibility, if not a strong probability, that la Bête was two or more wolves, I’m inclined to give Canis lupus the benefit of the doubt. Until about the last fifty years, people of European origin hated wolves with an intensity rarely leveled at other species. Through bounties and government-sponsored campaigns, we nearly annihilated an animal that rivaled our success, ranging most of the globe. We mowed them down from airplanes, strangled them with snares, and poisoned them with strychnine, all while calling them tricksters and cowards. We made them Satan’s minions, the beast within, and the avatar of a wilderness we demanded to conquer in the name of God. Yet if one believes the tale of a she-wolf raising Romulus and Remus, then we can thank the wolf for most of Western civilization. So, for now, I’m blaming the lion, who we at least had the decency to admire before skinning and who has probably taken far more children than the big, bad wolf ever did.

RESOURCES:

Lopez, Barry. 1978. Of Wolves and Men. Simon and Schuster. ISBN: 978-0684163222

Capstick, Peter Hathaway. 1981. Maneaters. Safari Pr. ISBN: 978-1571571175

Dixon, Debora P. 2013. Wonder, Horror, and the Hunt for La Bête in mid-18th Century France. Geoforum. 48: 239-248.

Todaro, Giovanni. 2013. The Man-eater of Gévaudan. Lulu Author. ISBN: 978-1291503401

Taake, Karl-Hans (2020). Biology of the “Beast of Gévaudan”: Morphology, Habitat Use, and Hunting Behaviour of an 18th Century Man-Eating Carnivore. ResearchGate.

Taake, Karl-Hans (2023). The 1767 French “Rapport Marin” – a Questionable Report about the Examination of an Allegedly Man-eating Wolf (Canis lupus). ResearchGate; pp. 1-16.